Hey, Big Spender

How the cost of legacy cores squeezes investment in innovation

The way that banks invest in IT tells you a lot about the industry.

At most incumbent banks, IT-based expenditure on growth and innovation is being squeezed by two other non-negotiable priorities within IT budgets: the need to keep the lights on and the cost of complying with non-discretionary regulation. For banks in this position, only one solution can ease the squeeze: modernizing legacy cores and adopting cloud-native software and development practices. By rationalizing IT operations in this way, banks can release more funding for innovation.

Let’s start with the cost of keeping the lights on. Among incumbents in the banking industry, as elsewhere, the IT budget is mostly spent on the compute, storage, networking, maintenance, upgrades, and human talent that enable this. According to Temenos Value Benchmark (TVB), an in-house program at Temenos that benchmarks how banks invest in technology, keeping the lights on typically accounts for 51% of the cash that banks funnel into IT every year.

CIOs adopt various strategies to control this spending, but keeping the lights on is a non-negotiable objective.

Making the technology changes required by new and updated regulation is also non-negotiable. In 2019, the banks participating in TVB typically spent 10.8% of IT funding on keeping up with regulatory changes. By 2023, they were allocating 15.8% of IT spending to the same job.

How much is left to invest in growth and innovation? (For TVB, this includes any investment that aims to improve the bank’s operations.) On average, banks worldwide allocate three out of every 10 IT dollars to these objectives.

These are average cost breakdowns for all 150 banks in TVB’s database. Around this average, the world’s banks fall into three camps, driven by their own, very specific decisions about IT investment. First, there are The Persistent Innovators: those who devote an above-average proportion of IT spend to innovation, regardless of how they invest the rest. In 2023, 40% of banks in TVB’s database qualified as members of this group.

The second group—26% of TVB banks—spends above-average amounts on compliance and below-average amounts on innovation. We might describe this group as the Big Compliance Spenders.

Finally, the third group – around one-third of TVB banks – struggle to contain the cost of keeping the lights on. They invest a below-average proportion of IT spend on both compliance and innovation. We might call this group the Legacy Strugglers.

In different ways, banks in all three camps face challenges in coping with the rising cost of adapting to regulatory change.

European bank regulation: an increasing burden

Over the past two decades, European banks have invested heavily in adapting to the European Central Bank’s Supervisory Review and Evaluation Process (SREP), which oversees capital requirements and risk management. Today, according to one estimate, banks based in the European Union face higher supervisory fees, larger capital requirements, bigger contributions to deposit and resolution funds and more demanding reporting obligations than their US counterparts.

In addition, European banks have been anticipating and reacting to new regulatory requirements in multiple areas, including payments (SEPA, Swift, PSD2), interest rates (Risk-Free Rates), data privacy (GDPR), tax (FATCA, CRS), accounting standards (IFRS, FASB) and operational resilience (Digital Operational Resilience Act). Most of these regulations come with hard deadlines that don’t slip. Many regulatory regimes are updated annually, creating recurring variable workloads.

Matthieu Charles, Vice President of Customer Strategy, Temenos, oversees Temenos Value Benchmark (TVB). He is certain that regulation is one of the factors forcing up overall IT expenditure in Europe. “In Europe, banks invest more in IT because the alternative of bigger teams is too expensive,” he says. But in addition, regulation is a big burden: banks spend a lot of time developing responses to it.”

Regulators increasingly expect banks to report on system resilience, availability, documentation, data usage, ESG, security and other aspects of their operations.

When new regulations emerge or existing ones are amended, the hunt begins to define which parts of the legacy codebase – often poorly documented – need to be adjusted.

Finally, there is the work involved in rewriting the correct sections of code and testing the results (which, as we’ll see, is not always a simple task).

The challenge of ageing, monolithic, core systems

Core banking applications built between the 1960s and 1990s are often described as monolithic, in the sense that all (or most) of their functionality is interconnected in opaque and unpredictable ways. In addition, these systems don’t operate in real time. The frequent absence of detailed documentation and years of patching and workarounds can create unanticipated dependencies and additional layers of risk.

Re-coding and testing a legacy application often resembles opening a can of worms.

Simply adding new parameters or revising existing ones can be challenging. (In legacy applications, the existing parameters are often coded within the software itself, which increases the risks of change.)

By contrast, modern applications based on microservices tend to be modular and composable. This means that changing software to accommodate new or altered regulation typically involves altering the dynamics in only one part of the application. As a result, re-coding and testing becomes far faster, and more secure and reliable. In addition, modern applications typically allow users to change parameters by using a simple user interface, rather than re-coding the application itself.

Modern core systems have other advantages. They come complete with the tooling and workflows that enable DevOps, CI/CD and cloud native software engineering. This enables not just accelerated Time to Market, but what we might call accelerated Time to Compliance.

There is more than time involved. It’s expensive to hire software engineers equipped with the increasingly rare skills of yesteryear. To some extent, focusing on these skills also detracts from the IT organization’s ability to focus on the skills of tomorrow. This matters because one of the most obvious ways to keep the flywheel of innovation in motion is to develop a reputation for investing in it. Apart from salary, as Stack Overflow’s Developer Survey confirms, the factor most likely to attract technology talent to work for your company is the prospect of working with exciting new technologies. (The same survey points out that 80% of developers dread the prospect of working with COBOL, the programming language most closely associated with ageing core systems.) In a similar vein, the biggest frustration of developers in employment is – yes, you guessed it – the technical debt associated with legacy systems.

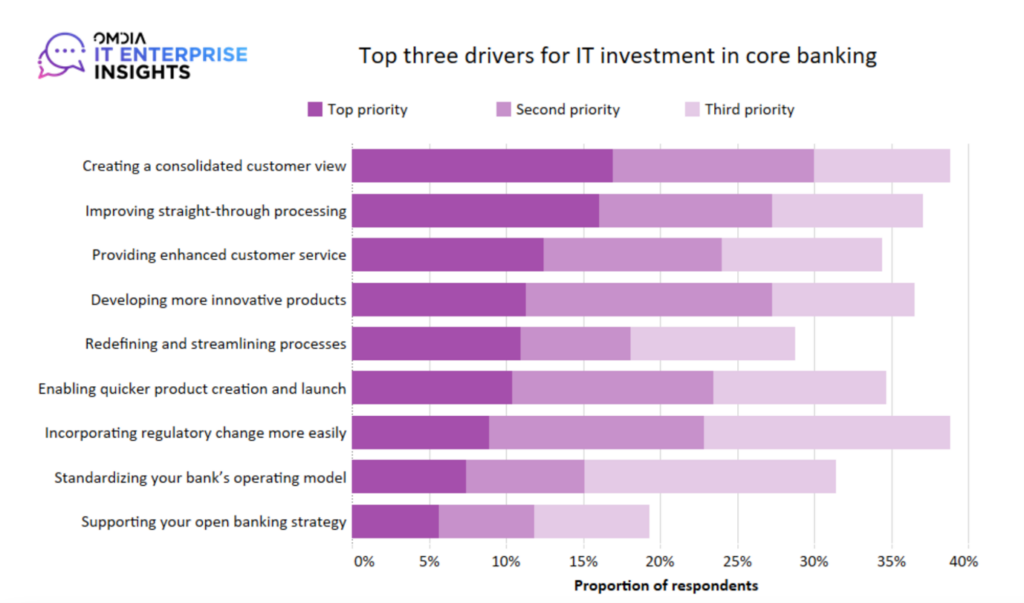

Banking executives who work in legacy environments understand that amending these core systems can be a slow and costly process. When Philip Benton, Principal Fintech Analyst at Omdia, recently published research findings on the drivers of core modernization, he understandably chose to focus on the objective that industry executives felt the most keenly (the need to create a single, consolidated view of the customer). However, given the opportunity to identify three top objectives of modernization, industry executives mentioned another objective – the desire to incorporate regulatory change more easily – just as frequently.

The case for economies of scale

There’s no question that dealing with regulatory change is a labour-intensive, industry-wide effort. This makes it the kind of challenge that can successfully be addressed by centralized third party service providers with the ability to create substantial economies of scale.

Temenos, for example, maintains a team of regulatory experts dedicated to monitoring regulatory changes and feeding new requirements to the software developers who build the company’s codebase and country model banks.

Serge Munten, Head of Business Transformation at Banque Internationale à Luxembourg (BIL), which recently shifted from a legacy in-house platform to Temenos for core banking and payments, describes this kind of service as “in a sense, the mutualization of the cost of [keeping up with] new regulations”.

As Cormac Flanagan, Head of Product Management, Temenos, puts it: “Banks running and maintaining their own core legacy systems have to do this work themselves. They get no economies of scale. And the IT funding available for innovation continues to come under pressure.”

“If you have a vendor like Temenos providing you with your core application, we are assessing the quantum of regulatory change and the deadlines involved. We’re continuously looking at what’s required to re-code, test and ship the regulatory changes across more than 150 territories. And we’re doing this not just for one bank, but for many banks, worldwide, on a continuous basis.”