How APSN Can Spell UDAAP

I know you’re thinking, “I took first-grade spelling, and I know that’s not right.” Alas, once again, that perk we offer our customers, “an overdraft program”, comes back to bite us in the back end. And this time, the back end is the literal processing of our items.

First things first, the FDIC applies the same standards as the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) and FTC in determining whether an act or practice is unfair under the respective statutes. An act or practice is unfair when it (1) causes or is likely to cause substantial injury to consumers, (2) cannot be reasonably avoided by consumers, and (3) is not outweighed by countervailing benefits to consumers or to competition. Public policy may also be considered when analyzing whether a particular act or practice is unfair.

The UDAAP risk related to the Approved Positive, Settle Negative (ASPN) transactions would occur because the customer has a reasonable belief that the funds are available at the time of the transaction and that no overdraft fee would occur.

The transactions that are being addressed in the APSN issue are POS transactions where the customer will be at a merchant location, have a transaction authorized as funds are available, and then once the actual settlement of the transaction comes through, the account ends up overdrawn because of subsequent transactions which cleared, and the customer is charged an overdraft fee for the transaction. When this occurs, it is considered an Authorize Positive, Settle Negative (ASPN) transaction and can land you in trouble with the regulators if not identified and cleared without a fee being charged.

Per the CFPB’s interpretation, this issue will often arise when the available balance is used to determine the balance used for potential overdraft decisions. This means if a charge is authorized into a positive balance and a hold is placed on the funds and additional transactions post in the interim to bring the balance negative, by the time the original transaction comes through, it is into a negative balance and charged a fee.

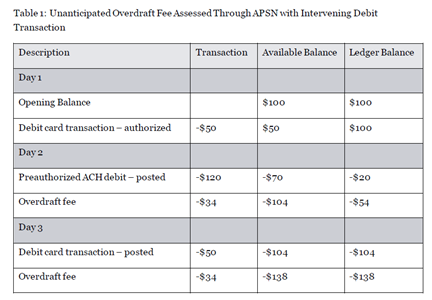

The scenario for when and how this can happen can be fairly complicated. Still, it is well demonstrated by the CFPB’s tables which show how a customer could be charged for two overdrafts that should really be one overdraft situation.

For example, as illustrated above in Table 1, on Day 1, a consumer has $100 in her account available to spend based on her available balance displayed. The consumer enters into a debit card transaction that day for $50. On Day 2, a preauthorized ACH debit that the consumer had authorized previously for $120 is settled against her account. The financial institution charges the consumer an overdraft fee. On Day 3, the debit card transaction from Day 1 settles, but by that point, the consumer’s account balance has been reduced by the $120 ACH debit settling and the $34 overdraft fee, leaving the balance as negative $54 using ledger balance, or negative $104 using available balance. When the $50 debit card transaction settles against the negative balance, the financial institution charges the consumer another overdraft fee. Consumers may not reasonably expect to be charged this second overdraft fee based on a debit card transaction that has been authorized with a sufficient account balance. The consumer may reasonably expect that if their account balance shows sufficient funds for the transaction just before entering into the transaction, as reflected in their account balance in their mobile application, online, at an ATM, or by telephone, then that debit card transaction will not incur an overdraft fee. Consumers may not reasonably be able to navigate the complexities of the delay between authorization and settlement of overlapping transactions that are processed on different timelines and impact the balance for each transaction. If consumers are presented with a balance that they can view in real-time, they are reasonable to believe that they can rely on it rather than have overdraft fees assessed based on the financial institution’s use of different balances at different times and intervening processing complexities for fee-decisioning purposes.

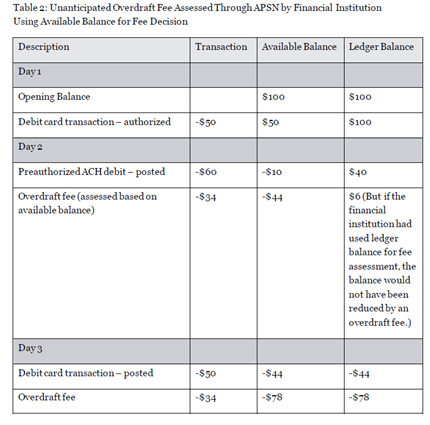

Certain financial institution practices can exacerbate the injury from unanticipated overdraft fees from APSN transactions by assessing overdraft fees in excess of the number of transactions for which the account lacked sufficient funds. In these APSN situations, financial institutions assess overdraft fees at the time of settlement based on the consumer’s available balance reduced by debit holds rather than the consumer’s ledger balance, leading to consumers being assessed multiple overdraft fees when they may reasonably have expected only one.

The following table (Table 2) shows an example of how financial institutions may process overdraft fees on two transactions. The consumer is charged an additional overdraft fee when the financial institution assesses fees based on available balance, because the financial institution is assessing an overdraft fee on a transaction that the institution has already used in making a fee decision on another transaction. By contrast, the consumer would not have been charged the additional overdraft fee if the financial institution used the ledger balance.

For example, as illustrated above in Table 2, on Day 1, a consumer has $100 in her account, which is the amount displayed on her online account. The consumer enters into a debit card transaction that day for $50. On Day 2, a preauthorized ACH debit that the consumer had authorized previously for $60 is settled against her account. Because the debit card transaction from Day 1 has not yet settled, the consumer’s ledger balance, prior to posting of the $60 ACH debit, is still $100. But some financial institutions will consider the consumer’s balance for purposes of an overdraft fee decision as $50, as already having been reduced by the not-yet-settled debit card transaction from Day 1. Thus the settlement of the $60 ACH debit will take the account negative and incur an overdraft fee. On Day 3, the debit card transaction from Day 1 settles, but by that point the consumer’s balance has been reduced by the settlement of the $60 ACH debit plus the overdraft fee for that transaction. If the overdraft fee is $34, the consumer’s account has $6 left in the ledger balance. The $50 debit card transaction then settles, overdrawing the account, and the financial institution charges the consumer an overdraft fee. The consumer would not expect two overdraft fees since her account balance showed sufficient funds at the time she entered into the debit card transaction to cover either one of them. But in this example, the financial institution charged two overdraft fees by assessing an overdraft fee on a transaction that the institution has already used in making a fee decision on another transaction. By contrast, a financial institution using ledger balance for the overdraft fee decision would have charged only one overdraft fee.

In the above scenario, the key is when using the temporary hold to determine the funds available for the second transaction. This particular situation could be resolved by determining if the overdraft would be paid were it not for the temporary hold. The difficult part is if a financial institution offers overdraft protection and the customer has opted in to Reg E POS and one-time ATM transactions, would they have known that the POS transaction was approved because the funds were available or that it was dipping into their overdraft funds.

There are a couple of avenues financial institutions are taking to try to eliminate this risk. The first is that there is a possibility that the financial institution’s core system may be able to distinguish good funds from those that are authorized into an overdraft program; then, you could continue to offer an opt-in overdraft program AND charge a fee for items paid into the overdraft program. However, if you are unable to distinguish between these funds, you may have to either not offer a POS/ATM opt-in program or not charge for any one-time POS/ATM overdrafts.